Drive through the village of Estero and look at the lush, landscaped gated communities, the upscale apartment complexes and the multitude of retail centers. It’s no coincidence that they are dominated by Mediterranean-style architecture and earth-tone colors. Community leaders nearly three decades ago had a vision for the then-sleepy community snuggled between Bonita Springs and unincorporated Lee County: They wanted Estero to look more like Boca Raton on the east coast than other sections of the county.

To reach that goal, leaders decided Estero was better off having its own government. The village incorporated 10 years ago, when the clock struck 12:01 a.m. Jan. 1, 2015.

“Leaders wanted to control their own destiny, what it was going to look like, what the lifestyle was going to be, what kind of development you wanted in the community,” says Jim Wallace, developer and Estero Planning, Zoning & Design Board member.

A path to distinction

A path to distinction

The village has retained the high standards that volunteer community leaders began. The board drills down on each project, sometimes picking apart potential developments it considers are not up to the village’s standards.

“The planning and zoning board has a reputation of being probably the toughest in five counties and probably one of the toughest in the state, and it’s because they want differentiation,” says Terry Flanagan, who moved to Estero from Chicago four years ago.

The board is an extension of what started at the end of the 20th century. Before 2000, “bubble plans” were common in the county, according to Forging a Better Path, a history of the Estero Council of Community Leaders and the creation of the village. Bubble plans provided few details and allowed a wide range of uses, said Mary Gibbs, the village’s community development director and former Lee County planner.

The forerunner of the ECCL, the Estero Concerned Citizen Organization, formed after a car dealership — with few design controls — was proposed on U.S. 41 near Fountain Lakes. The concerned citizens group developed the Estero Community Plan, which set standards for commercial development and required developers to hold public meetings before applying for zoning. Part of the plan involved creating a community review board, based on others in Boca Raton and in Boston, that would hash out projects with developers before the project would go to the county for approval.

The collaboration began to change around 2012, about the time Commissioner Ray Judah lost reelection, said Jim Shields, who became involved with the ECCL when he moved to Estero in 2004. Developers targeted Judah, a former planner and a critic of some of the growth happening in the county.

Gibbs, who was working for Lee County at the time, said the community planning program was cut for budget reasons around that time. The county no longer was going to provide the level of community assistance it once had, so the program became one-size-fits-all.

“I think it would be very different,” Gibbs said of Estero if it hadn’t incorporated. “It would be less like Estero and more like the rest of Lee County.”

Dialed in details

Dialed in details

Looking more like Estero and less like Lee County was a challenge for builders.

“There were developers who were upset because they never on the west coast had come up against the kind of standards that Estero had,” Wallace says. “But when you have a growing market, retailers want to be in it, developers want to be in it, so you raise your own standards to be allowed to do that.”

Lee County doesn’t have the stringent architectural review, said Keith Gelder, vice president of land with Stock Development. He was responsible for overseeing the mixed-use development of Estero Crossings off Corkscrew Road.

“There’s a lot more flexibility in terms of design. We would have gotten much faster through the process, but in the end, I think we are really happy with the product and the outcome of how it turned out,” he says.

Going through Estero’s approval process can make a project more expensive. “In general, naturally, but what it does do is produces high-quality product, which we’re always supportive of,” Gelder says.

Alexis Crespo, vice president of planning at RVi Planning, has worked on 20 to 30 projects in Estero, some before and some after it incorporated, she said. She called the design review board “very effective, formidable, predictable, committed to a vision and consistently tied to high quality.”

The design board has a mix of experienced board members — a landscape architect, an architect, a developer, a civil engineer and a commercial Realtor, Crespo said.

“They know what they want,” says Joe McHarris, a local architect and former planning board member. “If you think you can push them and wear them down, it won’t happen.”

He said the board has been hard on him when he presents projects, and he helped write some of the rules.

McHarris is not alone, especially when it comes to national companies and big-box stores that have their own colors and designs.

“There are people who come to us and say, ‘We have a national model and that’s what we’re going to stick with.’ If that’s so, you are going to keep coming back and coming back,” Wallace says.

Walmart was one of the early big-box stores that wanted to open in Estero. The retailer set a precedent for the Estero Community Planning Panel, which created regulations for big-box stores. Walmart got beaten up during its early presentation because it showed a design it wanted to build, Wallace said. But it had backup plans for what it would be allowed to build; the building at the northeast corner of U.S. 41 and Estero Parkway looks different than other Walmarts with its Tuscan-style front.

Mini warehouses are another example of Estero’s tougher standards. They are called stealth storage facilities because they look more like office buildings than storage facilities. The Lock Up facility across from Coconut Point set the tone.

“We had another storage unit, the CubeSmart on Ben Hill Griffin, come in after that and we told them, ‘You need to make it look like an office building,’ and who would have thought you could make a mini warehouse look beautiful? But they did,” Gibbs says.

Things to come

Things to come

Expect the next 10 years to look much like the last 10. The village has about 10% vacant land left for development, Gibbs said. Most of it will be filled with multi-use projects comprising apartments, condos, offices and retail.

Projects on the drawing board include 2,500 residential units, four hotels, a 23-story high-rise and 300,000 square feet of commercial use, according to a presentation made earlier this year.

Gibbs expects to start seeing redevelopment of some of the older developments including Coconut Point mall.

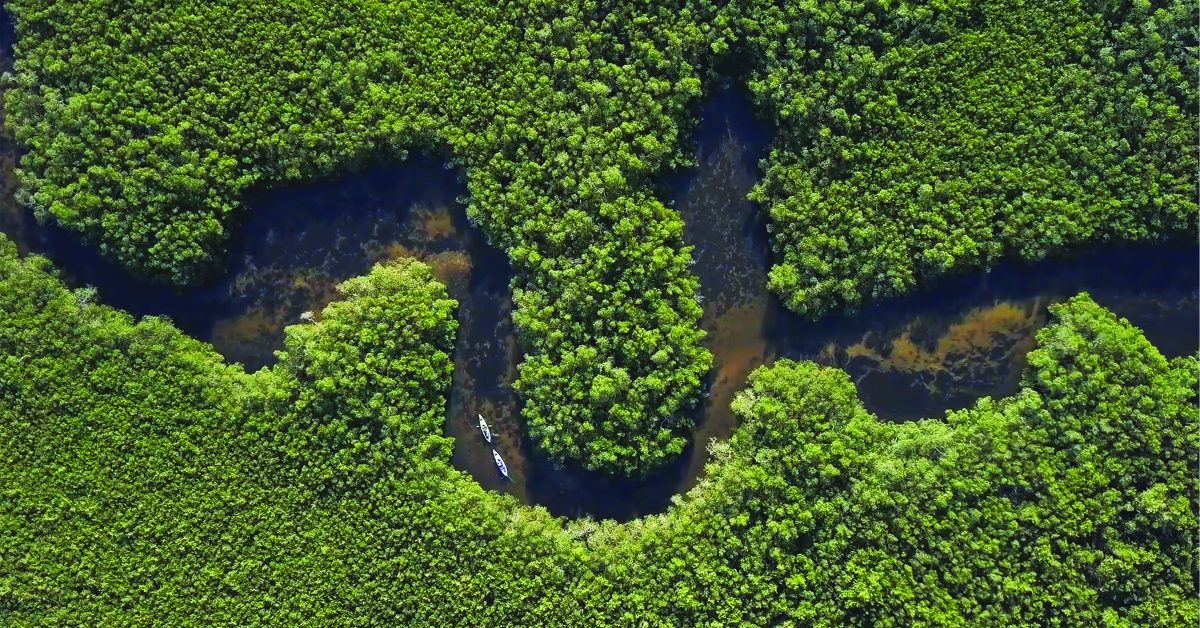

The village has its own projects planned, one goal of which is to develop its identity as a village instead of a bunch of gated communities. It’s building a sprawling sports park next to Estero High School and an Estero River Park.

Don Madey has lived in the Breckenridge community in Estero for 17 years. He said he has lived all over the U.S., including Boca Raton.

“This reminds me very much of Boca,” he says. “If their goal was to be like Boca, they’ve been successful.”

Estero stats

Estero stats

Population: 37,908

Area: 30 square miles

Communities: 61

Median Household Income: $100,459

Persons 65 and older: 50.7%

Source: Estero, U.S. Census Bureau

The development process

The development process

All land has a zoning designation, either commercial, residential, agricultural or mixed-use. If landowners want to change the zoning use, they have to get approval from the village. If they want to build within the current zoning, they have a couple of documents to follow:

The Comprehensive Plan

It’s the vision of how Estero intends to balance residential, commercial, public and reserve lands. If a developer wants to build something outside the plan, approval is required from the village council after a review by the Planning, Zoning and Design Review Board.

The Land Development Code

A technical document that details the rules builders and developers must follow to match the Comprehensive Plan’s vision. All developments must present their architectural plans for buildings, site plans, permanent signage and more for review to make sure they meet the standards of the code.

Planning Staff

Estero’s staff developed the Comprehensive Plan and the Land Development Code. The staff reviews developers’ plans and makes their recommendation to the Planning, Zoning and Design Review Board.

Planning, Zoning and Design Review Board

The board holds a public hearing and either sends the plans back to the developer for changes or gives a recommendation to the village council.

Village Council

It can either approve the development or deny it.

Source: Engage Estero

Other reasons to incorporate

Other reasons to incorporate

Fear of not being able to control its own destiny wasn’t the only reason Estero incorporated. The community was paying more in taxes than receiving in services, said Jim Wallace, who developed several projects in Estero; and residents feared that Bonita Springs was going to annex some of the area’s most valuable properties.

Bonita incorporated in 2000 and agreed not to annex anything in the Estero Fire District boundaries for five years, according to Forging a Better Path, a history of how Estero was created. After the agreement expired, Bonita unsuccessfully tried to extend its northern boundary to Williams Road; in 2007 it agreed not to try to annex any Estero land if Estero agreed not to incorporate. The agreement lasted for 5 1/2 years, but then Bonita Springs annexed 121 acres owned by WCI Communities and Coconut Point Marina and the Hyatt in 2013.

Members of the Estero Council of Community Leaders thought the only way to keep Bonita from encroaching more on Estero was by incorporating. The proposal overwhelmingly passed on the November 2014 ballot.