For food banks and their partnering hunger-relief agencies that help feed thousands of Southwest Florida residents facing hunger or food insecurity, recent federal funding cuts are posing significant challenges.

And those challenges will be multiplied, organizations say, if major cuts are made in President Donald Trump’s proposed budget to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps. At press time, Trump’s budget had been passed by the United States Senate and sent back to the House of Representatives with 20% in recommended cuts to SNAP.

Food banks in SWFL and across the country have been dealing with cuts imposed by the federal Department of Government Efficiency earlier this year, seeing reductions of more than $1 billion affecting programs including the Local Food Purchase Assistance program and The Emergency Food Assistance Program.

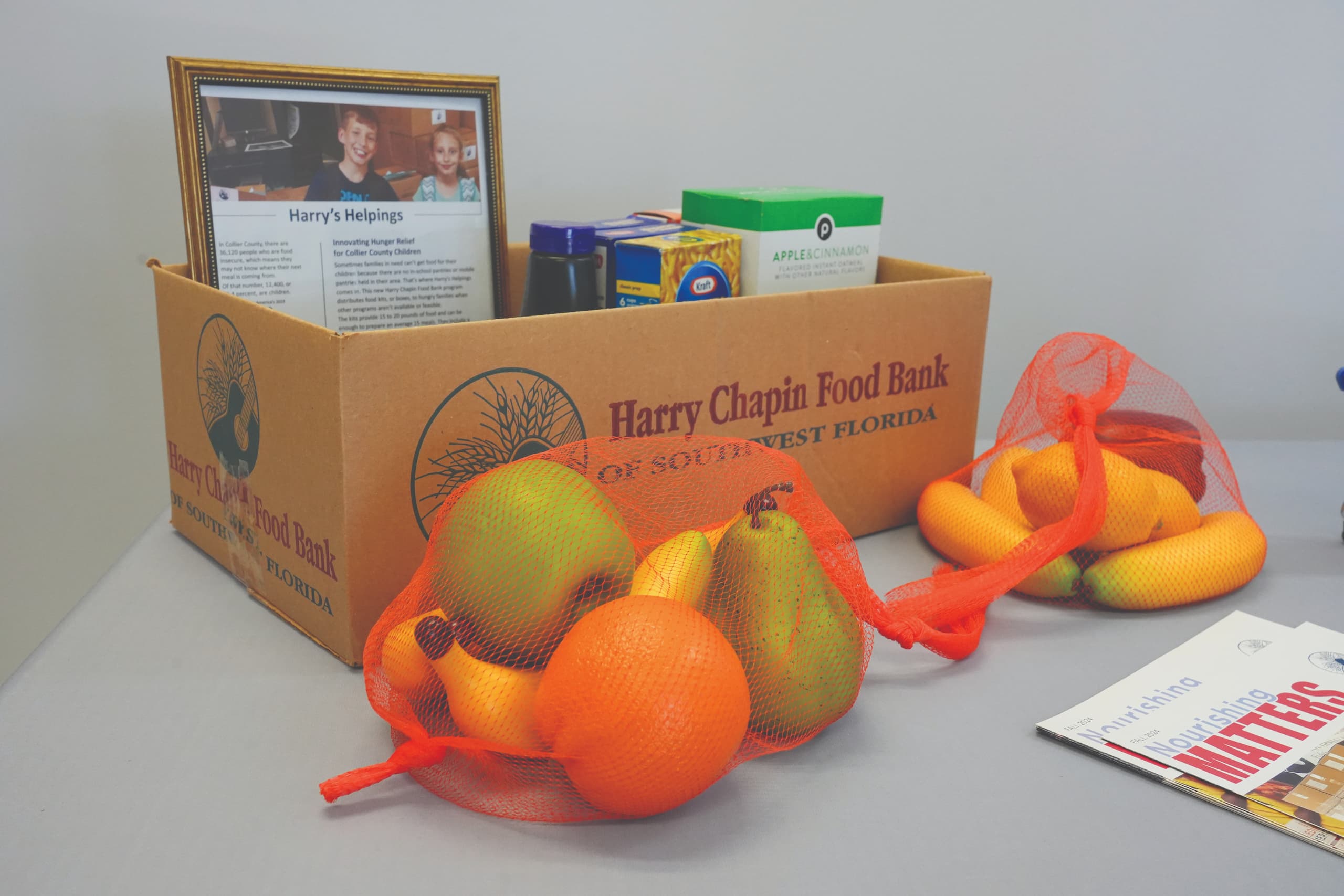

Harry Chapin Food Bank: supply down, demand up

Harry Chapin Food Bank of Southwest Florida, with distribution centers in Fort Myers and Naples, was founded in 1983. The largest food bank in the region, HCFB works with partner agencies to distribute food to more than 250,000 people monthly in Charlotte, Collier, Glades, Hendry and Lee counties.

More than 39.5 million pounds of food — the equivalent of 32 million meals — was distributed across the region last year, according to the organization’s 2024 Community Impact Report.

HCFB is serving about 75% more people now than it did before the COVID-19 pandemic, according to president and CEO Richard LeBer.

He said the organization receives about 20% of its food from the LFPA and TEFAP government programs, which have been cut 20%. LeBer said he anticipates another 20% reduction next year.

“We are in better shape than some food banks because about 80% of our food is privately donated,” LeBer said in a recent interview.

He said the single largest source of food supply is grocery stores, followed by farms.

“Our network has trucks at every major grocery store in Southwest Florida pretty much every day, picking up food that the store knows they’re not going to be able to sell and bringing it back to make available to people who are hungry,” LeBer said. “And that amounts to millions of pounds of food every year.

“Our second largest source of food is farms, and we’re bringing in food from farms all year round by the truckload. Again, millions of pounds of food.”

But the cuts definitely hurt, LeBer said, during a time when more and more people are facing food insecurity while the costs of housing, insurance, medical care, transportation and food are all rising.

“It doesn’t help at a time when inflation is hot and heavy, and we’re seeing more people than normal,” he said. “And we think that it’s likely to increase, to have our food supply cut back somewhat. It just means we need to work that much harder.”

“It doesn’t help at a time when inflation is hot and heavy, and we’re seeing more people than normal,” he said. “And we think that it’s likely to increase, to have our food supply cut back somewhat. It just means we need to work that much harder.”

LeBer said he is concerned about the consequences on both the demand side and on the supply side because many of the people served by the food bank rely on a number of other social programs, including SNAP.

“We don’t get anything [from SNAP], but many of the people we serve do,” LeBer said. “And if those programs get cut, then those people are going to be short of a supply of food that they were accustomed to having and they’re likely going to come to us looking for assistance.

“The likelihood is that the demand for food help goes up at the same time that supply goes down. So, that certainly will be challenging.”

He said best estimates based on the current budget say that Southwest Florida could lose about 33 million meals that would otherwise be provided by SNAP in a year.

“To give a sense of comparison for that, it’s about as much again as we distribute in a year,” LeBer said. “So, if that’s a gap we have to fill, we would have to double the amount of food we distribute.”

Most of the people served by HCFB and its partner agencies are working families from all walks of life, trying to keep up with the high cost of living in Southwest Florida, LeBer said.

“Roughly 70% of the people we serve are in working families, and there’s a lot of kids we serve,” he said. “The other big category would be seniors, particularly seniors on fixed incomes, and seniors with expensive chronic medical conditions.”

Collier County partner agencies feel the pinch

While HCFB does distribute some food from its locations in Fort Myers and Naples, LeBer said 80% of its food is distributed through 175 partner agencies throughout its five-county area that it delivers to, free of charge.

In Collier County, HCFB delivers food to 35 partner agencies for distribution, including St. Matthew’s House, Meals of Hope, Salvation Army and Catholic Charities-Collier in Naples, and Our Daily Bread Food Pantry in Marco Island.

At Our Daily Bread Food Pantry, Executive Director Evelyn Rossetti-Ryan said she is seeing the effects of the cuts that have been enacted so far, and shares LeBer’s concern about potentially significant cuts to SNAP.

She said as of now she can only speculate about how many of the food pantry guests that are served will be affected by SNAP reductions.

Our Daily Bread serves about 73,000 households in Naples and Marco Island each year through repeated visits, Rossetti-Ryan said, distributing more than two million pounds of food. The food pantry also partners with Collier County schools, providing weekend meal bags with breakfasts and lunches for students who need them.

“The households that we serve, many are working families or individuals just working hard to make ends meet,” Rossetti-Ryan said in an interview. “Many of them have children, and school-age children, so we know there’s going to be widespread impact and it could very well affect the majority of our guests. We are still waiting to hear what the final answers and outcomes will be, so we’re bracing ourselves for that.”

“The households that we serve, many are working families or individuals just working hard to make ends meet,” Rossetti-Ryan said in an interview. “Many of them have children, and school-age children, so we know there’s going to be widespread impact and it could very well affect the majority of our guests. We are still waiting to hear what the final answers and outcomes will be, so we’re bracing ourselves for that.”

Rossetti-Ryan said that the decline in donated food is having a direct consequence “because the need hasn’t declined.”

“The resources available to meet those needs has declined, and there’s still great uncertainty,” she said. “Of course, with great uncertainty there’s also great concern.”

She described the food pantry’s typical guests — or “neighbors in need” — as hardworking people who “help make a community run.”

“They are people who help us build houses, clean houses; landscapers, roofers, Uber drivers, hairdressers — you name it,” Rossetti-Ryan said. “We’ve seen many different people in different professions coming to us, and they’re striving and struggling to make ends meet.”

And it’s not just food that Our Daily Bread seeks to provide to its guests, she said.

“We define ourselves as ‘We offer food, encouragement and hope,’ because we do,” Rossetti-Ryan said. “We don’t judge anyone who comes to us. In fact, we try to offer encouragement. We try to offer hope.”