The first known franchises were kings and nobles who granted local peasants protection of the castle and the right to farm outside castle walls. The serfs gave a portion of their crops to the landowner in exchange for permission to farm.

“The kings and parishioners said this was a pretty good deal, protection of the castle in exchange for royal tithes, which became the word ‘royalties,’” says Robert L. Purvin Jr., CEO of the American Association of Franchisees & Dealers. The AAFD represents the rights and interests of franchisees and independent dealers in the United States.

Gulfshore Business asked successful—and sometimes not so successful—Southwest Florida franchise owners to describe their experiences. The primary takeaway, they said, is that stone parapets and royal accountants have been replaced with gleaming corporate headquarters and lawyers who design franchise agreements that aren’t always in the best interest of franchisees.

For instance, franchise companies come with economies of scale, which means franchisees can buy everything from cleaning supplies to employee uniforms to food products and menu ingredients at a volume discount. Likewise, the cost of the company’s national advertising and marketing campaigns can be shared among hundreds of store owners.

But store owners bound by franchise agreements often can’t negotiate better prices for goods and services. “When you buy a franchise, you become a captive buyer for what they sell you,” Purvin says. “Franchisees have to buy from sources dictated by the franchisor. They wield their authority to dictate and profit it from that source of supply.”

EVERYONE’S CAUTIONARY TALE

Nearly every expert we spoke to pointed to Quiznos and its rapid decline between 2007 and 2017. The collapse of the company allegedly led one California franchise owner to take his life. He blamed the company in his suicide note, which fellow Quiznos franchisees posted online.

The company’s franchise agreement required franchisees to buy high-priced food, ingredients and paper goods from American Food Distributor, a subsidiary of Quiznos’ corporate office. During the same period, Quiznos set the price for sandwiches and other menu items too high for customers, which franchisees said also cut into profitability. A group of 28 Wisconsin Quiznos franchisees sued the company for hindering profitability.

And the numbers bear that out: American Food Distributor (Quiznos Inc.) took in $500 million in 2006 while over time, the 4,700 Quiznos locations had shrunk to fewer than 400 stores, a loss of 90%. “Those 4,700 locations averaged just $400,000 in revenue a year. “The high food costs made it tough for them to make a profit,” Restaurant Business Online reported. Scores of Quiznos sub shops closed in Southwest Florida.

“Quiznos is a perfect example,” Purvin says. “They destroyed their franchise by abuse of the supply chain.”

FINDING FRANCHISE FITS

There’s a lot of investment money floating around Naples, Fort Myers and other SWFL communities. Naples alone is home to at least six billionaires and, according to Cityinfo.com, 12,000 households made up of millionaires.

If one is considering a franchise, “The first thing I would suggest is to talk to other franchisees in that concept,” says Michael Koroghlian, Dunkin’ franchisee. “They will tell you the truth.”

Koroghlian is just one of hundreds, and possibly thousands, of SWFL investors who devote their wealth, time and honor to their franchises—only a sliver of which are restaurants, by the way. Fran- chise.com lists plenty of non-food franchise opportunities in SWFL, and the cost associated with getting into each: Dickey’s Barbecue Pit ($100,000), Minuteman Press ($50,000), The UPS Store ($75,000), MaidPro ($75,000), as well as numerous tax services, medicinal marijuana outlets, auto repair shops, home health care services … name it, it’s franchised. That list also includes a distinctive franchise for regions such as SWFL that abut large swaths of the natural world, i.e., the Everglades. It’s called Critter Control ($50,000), the only wildlife management firm with offices coast-to-coast. “When it comes to nuisance wildlife,” its blurb goes, “homeowners, businesses and municipalities choose the professionals at Critter Control nuisance wildlife control to help protect their property.”

Koroghlian is just one of hundreds, and possibly thousands, of SWFL investors who devote their wealth, time and honor to their franchises—only a sliver of which are restaurants, by the way. Fran- chise.com lists plenty of non-food franchise opportunities in SWFL, and the cost associated with getting into each: Dickey’s Barbecue Pit ($100,000), Minuteman Press ($50,000), The UPS Store ($75,000), MaidPro ($75,000), as well as numerous tax services, medicinal marijuana outlets, auto repair shops, home health care services … name it, it’s franchised. That list also includes a distinctive franchise for regions such as SWFL that abut large swaths of the natural world, i.e., the Everglades. It’s called Critter Control ($50,000), the only wildlife management firm with offices coast-to-coast. “When it comes to nuisance wildlife,” its blurb goes, “homeowners, businesses and municipalities choose the professionals at Critter Control nuisance wildlife control to help protect their property.”

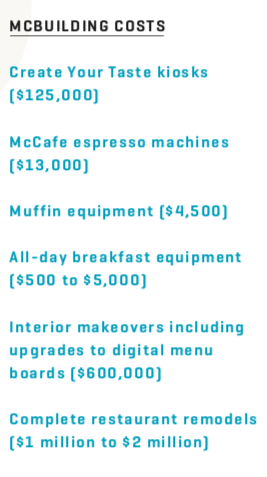

An initial franchise fee, of course, does not represent the true cost of running a franchise in the United States. McDonald’s, for instance, might require a $45,000 fee to get in, but franchisees must find between $1.1 million to $2.2 million to lease or construct the “Mcbuilding,” buy signage and cover other costs, such as paper goods, uniforms, beef, buns and more ingredients. There are additional required costs, too, when McDonald’s Corp. adjusts its product line, including upgrades to IT systems and that state-of-the-art digital menu board. Bloomberg News lists a few of the items McDonald’s franchisees have purchased on directions from the home office.

An initial franchise fee, of course, does not represent the true cost of running a franchise in the United States. McDonald’s, for instance, might require a $45,000 fee to get in, but franchisees must find between $1.1 million to $2.2 million to lease or construct the “Mcbuilding,” buy signage and cover other costs, such as paper goods, uniforms, beef, buns and more ingredients. There are additional required costs, too, when McDonald’s Corp. adjusts its product line, including upgrades to IT systems and that state-of-the-art digital menu board. Bloomberg News lists a few of the items McDonald’s franchisees have purchased on directions from the home office.

Koroghlian and other SWFL franchise operators recommend studying the latest version of the company’s Franchise Disclosure Document (FDD), which details the franchisee’s rights and obligations, as well as expected costs and other requirements.

The International Franchise Association said the FDD should describe, among other things, the biographies of the corporate officers, including any criminal or civil legal action against them. The booklet (Dunkin’s is 680 pages) also must clearly delineate fees and other costs as well as territory, trademarks, patents, advertising, the obligations of the franchisee and when the home office can step in. It creates guardrails for both home office and franchisee, so study it carefully.

Experts also recommend prospective operators talk to an attorney who specializes in franchise contracts.

After all, Purvin says, “The franchisor has a cadre of lawyers.”

ROBERT LYONS, Tide Dry Cleaners franchisee: “I was not on the operating side of dry cleaning, but that’s why franchises have platforms and processes in place to succeed.”

BUILDING ON BRAND AWARENESS

BUILDING ON BRAND AWARENESS

Robert Lyons is president and CEO of Consolidated Cleaners Inc., which operates more than a dozen Tide Dry Cleaners stores—a new franchise concept created by Proctor & Gamble Co., which, of course, develops Tide detergent and other familiar home products.

He and his two business partners wanted to franchise a brand that everyone could in- instantly recognize.

“Most franchises start as a burger place; no one knows anything about the product,” Lyons says. “With Tide, you have extreme brand recognition. It’s been a popular product almost 70 years. The smell and the quality of clean you get with it, that translates into extremely positive customer response.”

Lyons, new to dry cleaning (he was a resort development consultant) researched Tide Dry Cleaners’ operations, to see what it takes to run one of the units. “I was not on the operating side of dry cleaning, but that’s why franchises have platforms and processes in place to succeed,” he says.

Lyons, new to dry cleaning (he was a resort development consultant) researched Tide Dry Cleaners’ operations, to see what it takes to run one of the units. “I was not on the operating side of dry cleaning, but that’s why franchises have platforms and processes in place to succeed,” he says.

The company is not your parents’ dry cleaners. In addition to being environmentally friendly (no petrochemicals), it allows a customer to place an order using a smartphone app and be notified when clothes are ready for pickup at a store or have been delivered to a locker in the building where they live or work.

According to Lyons, Consolidated’s 13 Tide Dry Cleaning stores—in such areas as Fort Myers, Naples, Estero, Sarasota, Delray Beach and elsewhere—not only serve individual customers, but also dry clean and deliver linen, uniforms and other items for restaurants, country clubs, health clubs, office buildings and other business clients.

THE RIGHT PEOPLE ARE KEY

Franchise agreements often require the investor be heavily involved in running the operation; when several invest, as in Consolidated’s case, one investor becomes the operations guy. He or she, in turn, must hire and train managers for new stores.

“I’m the operating partner; you’re not going to put in money and the franchise will operate itself,” Lyons says. “I spent the first two years working the front counter and making it my own. It helped us develop our customer service philosophy.”

That gave him the framework to train managers to open, and run, additional units.

“We have five general managers who started in our first store in Naples,” he says. “It allows us to grow quicker, develop our management talent and open other locations, with confidence. Nineteen of our managers come from within our organization.”

“The No. 1 thing, without great people you’re not going anywhere,” Koroghlian agrees. “I have employees from Fort Lauderdale who have moved their whole families and been with me for many, many years. It’s an unbelievable team that has allowed us to grow.”

PIECE OF THE PIE: No rookie when it comes to managing franchises, Ralph Desiano faced issues when he attempted to franchise his Naples Flatbread concept.

A FRANCHISE MISFIRE

Ralph Desiano, the well-known and respected owner of Naples Flatbread Kitchen & Bar in Estero, has played in the franchise equivalent of the Major Leagues. His Corkscrew Road location is now his only restaurant, and he says he couldn’t be happier. “I started a family and like being closer to home with some time on my hands,” Desiano says. “I’m also blessed to have the best general manager in this market. He performs at a high level, and he manages some solid folks, too.”

After opening his first Flatbread in 2009 and then growing the company operations to five units (including two in Tulsa, Oklahoma), he sought to open a franchise in Sarasota. Again, he is no rookie when it comes to man-aging franchises. He was vice president of operations for Pizzeria Uno overseeing company and franchise locations, and then chief operations officer of Briad Group, the largest TGI Fridays franchise organization in the country. In spite of all that experience, his one attempt at franchising his own brand didn’t work. The problem: an inexperienced investor who insisted on running operations.

“It was an absolute disaster,” he says. “The only way I would sign the deal was that the franchisee would hire a team of experienced restaurant managers and then have them go through the complete training program. Then days before opening, he fired the entire management team, brought his brother down and he and his brother started to run it. You can guess the rest of the story, absolute disaster.”

Desiano now has time to focus on his flagship Estero location, with its greaseless kitchen and cutting-edge cooking equipment. His enhancements—including Clicquot and other quality wines, bottomless mimosas and a menu filled with shaved top sirloin, “drunken shrimp” and other artistic culinary items, has earned him a No. 1 rating on TripAdvisor.

He plans to install a self-service tap wall, where customers can wave a smartphone app or key fob over a sensor that activates tap handles that dispense specialty beer, wine and cocktails. The wall will dispense non-alcoholic beverages, too, including nitro coffee and kombucha drinks. Customers also can order the same items from their waiter.

“We’re about to do some interesting things in the next month,” Desiano says, “because I have time now to introduce them.”

But don’t count Desiano out of growing again. “I am hopeful we can get back out there and show the merits of a Naples Flatbread franchise.”

REACH OUT FOR SUPPORT

“Our proudest achievement is the development of our franchising standards,” says Purvin of the American Association of Franchisees and Dealers, which was founded during a business conference in Naples three decades ago. “Franchisors want you to pay a royalty burden, they tell you they have a brand people love, they tell you, ‘We have buying power, we save you money,’ but is the home office really doing what it can to see that you succeed?”

The AAFD and other independent franchise support groups maintain a list of lawyers and experts to answer questions from prospective investors. Though franchisees create their own regional support organizations, such as the Sam Houston McDonald’s Franchise Group in Texas, unallied franchise organizations like AAFD can provide advice on the pathway to franchising.

“The AAFD strongly recommends that you seek legal counsel experienced in ad- vising franchisees to help you to review and negotiate any franchise opportunity,” Purvin says. “Our members can receive free initial legal consultations.”

Purvin, author of the book The Franchise Fraud, recommends prospective franchisees research the ins and outs of franchises, information and data that is easily found on the Internet. The AAFD’s “Franchisee Bill of Rights” is a good place to start, he says. Some of the 14 points in the Bill of Rights are listed at the right.

The franchise business model has been around for centuries, but multiple supply channels, expensive marketing programs and complex legal agreements make for tricky ground. Study the Franchise Disclosure Document carefully, ask franchisees what they think and connect with experts before taking the leap.

“Owning and operating a franchise is not for everyone,” Desiano says. “The rewards are great, but the hours are long. You become part of a company family.”

HOLE IN ONE: Naples resident Michael Koroghlian has built three Dunkin’ locations in the Naples area and four in Fort Myers, and plans to launch another six in the area.

DUNKIN’ AND DEVELOPIN’

Michael Koroghlian of Naples researched Dunkin’ Donuts, now referred to simply as Dunkin’, before he bought his first one in Fort Lauderdale in 2007.

After spending a decade as an investment banker in Manhattan, he wanted his own business. “I just loved Dunkin’ Donuts while I was at Boston College,” the businessman says. “I found one store for sale in Fort Lauderdale and decided to take a chance. It was an old location right on Fort Lauderdale Beach, and it was about to shut down.

“I gutted it, did a complete renovation on it, and made it look brand new,” Koroghlian says. “It turned out to be a great store. I continued to grow from there and wound up buying or building another 25 stores in Broward County.”

He then sold those units to the largest Dunkin’ franchisee in the world, but realized he was too young to retire, he said. He moved to Naples, and now owns more than two dozen Dunkin’s, including 16 in Southwest Florida and the ones in the Keys. Incidentally, he didn’t know it at the time, but his first employee in Fort Lauderdale, Kassie, would become his wife. She works local causes, spreading the word about water safety and kids, for instance.

Koroghlian would not have committed to Dunkin’ if he didn’t trust the corporate offices as a business partner. And a commitment it is. “It doesn’t stop,” he says. “The minute my stores close, we start making donuts, close to 20,000 every day.”

The Quiznos debacle illustrates the need for franchise agreements that are beneficial to both sides, Koroghlian said.

The Quiznos debacle illustrates the need for franchise agreements that are beneficial to both sides, Koroghlian said.

“Dunkin’ does a great job watching out for the franchisee; their priority is to ensure we are profitable, which helps them build their brand,” he says. “The corporate people and I have a relationship as good as I’ve seen in any franchise relationship.”

Though Koroghlian has built three Dunkin’s in Naples, four in Fort Myers and plans

to build another six, the corporate Dunkin’ office has final call on where they can open. “You don’t want stores opening up on top of each other,” he says. “Dunkin’ looks at every deal to minimize or ensure it has zero impact on another franchisee.”

POINTS IN THE FRANCHISEE BILL OF RIGHTS

- The right to equity in the franchised business, including the right to meaningful market protection

- The right to engage in a trade or business, including a post-termination right to compete

- The right to trademark protection

- The right to competitive sourcing of inventory, product, service and supplies

- The reciprocal right

to terminate the franchise agreement for reasonable and

just cause, and the right not to face termination, unless for cause

EIGHT THINGS TO LOOK FOR IN A FRANCHISE OPPORTUNITY

1. Is the franchising company primarily interested in distributing products and services to ultimate consumers, or is it more interested in selling franchises?

2. Is the franchising company dedicated to franchising as its primary mechanism of product and service distribution?

3. Is the franchising company producing and marketing quality goods and services for which there is an established market demand?

4. Does the franchisor have a well-accepted trademark?

5. Does the franchisor have a well-established, well-designed business plan and marketing system that includes and promises substantial and complete training and overall franchisee support?

6. Does the franchisor have and prize good relationships with its franchisees?

7. Does the franchisor provide sales and earnings projections, and other financial performance data which demonstrates an attractive return on investment?

8. Does the franchisor support the protections set forth in the AAFD’s Franchisee Bill of Rights and agree to respect these rights as they apply to your franchise?

(Source: American Federation of Franchises and Dealers)

– John Guerra