Many of the world’s logistical problems have been justly blamed on the global pandemic and its ripple effects, and many people consider the ongoing commercial pilot shortage as just another example. However, this shortage was forecast to happen long before anyone heard of COVID-19.

Captain Lee Collins, senior vice president of industry and government affairs with Paragon Flight Training, said that the airline industry knew as far back as 2012 that there would be a commercial pilot shortage by 2017 or 2018.

So, if we can’t blame the pandemic for this one, what caused this shortage—and why is everyone noticing now, coincidentally as the world fights a pandemic?

Collins believes one of the multiple causes is that the number of airlines and routes have increased, creating higher demand. Another big contributing factor is that in the mid-’80s through 1990, airlines were hiring pilots at their largest rate, creating a giant swell that would be leaving the industry in the 2010s because of the mandatory retirement age of 60.

Since then, the retirement age for pilots was raised to 65 in order to combat the shortage issue. In July, South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham proposed a bill to raise the age again to 67. Collins, a full supporter of this bill, said he would feel completely safe having a pilot older than 65 flying himself and his family.

“Senior pilots are required to have physicals twice a year and recurrent training. The FAA is always monitoring,” says Collins.

International Air Transport Association Head of Corporate Communications Perry Flint breaks down the pilot shortage into long-term and immediate factors.

One that has perennially affected attracting new personnel is the cost and time it takes to become a pilot. Pilots have to build 1,500 flying hours once they get their license, and schooling cost runs in the low six figures, Flint said.

The industry also used to get large numbers of military pilots who were already trained to operate aircraft—“The military was such a strong conduit to become a pilot,” says Flint—but that is no longer the case. There was also a shortage of U.S. Air Force pilots, and the military started pilot retention, which kept the pilots in the military and not at commercial airlines, Collins said. Plus, more and more pilots in the military were being trained to fly drones and not passenger aircraft, which meant the transition from military to commercial airliners wasn’t as seamless as it once was.

“Back in the day, 40 to 50% of pilots came from the military. From 2015 forward, that dropped significantly,” says Collins.

The immediate factors, Flint said, are directly linked to the pandemic, which led to the parking of thousands of aircraft. Many pilots also accepted early retirement packages and furloughs. Training, which had normally included flight simulators that ran 24/7/365, paused. Some airlines also retired fleets of aircraft, leaving those crews to have to be trained on entirely new fleets.

The industry is trying to address these issues, and Flint believes it will continue to sort itself out.

Collins said there were steps being taken to hire and train more pilots before the pandemic hit, but once it did it slowed training, putting the industry even further behind than it already was.

Since then, airlines have enhanced salaries and benefits, created career tracks and done all they can to attract people. They have also started reaching out to high school students, broadening their net and trying to attract them younger, Collins said.

“When I started, you wouldn’t get to the major airlines until your mid-30s,” says Collins.

Now, students can be accepted into the regional airlines in their 20s, and make it to the major airlines when they are about 30. With programs like Paragon Fast Track, people can get a license in a year to 18 months, be working for a regional airline in three to four years and be at a major airline in an additional three years.

But in the meantime, occasional delays remain a fact of life.

“The issues are across the industry,” says Flint, “and there is no silver bullet solution.”

You’re Grounded

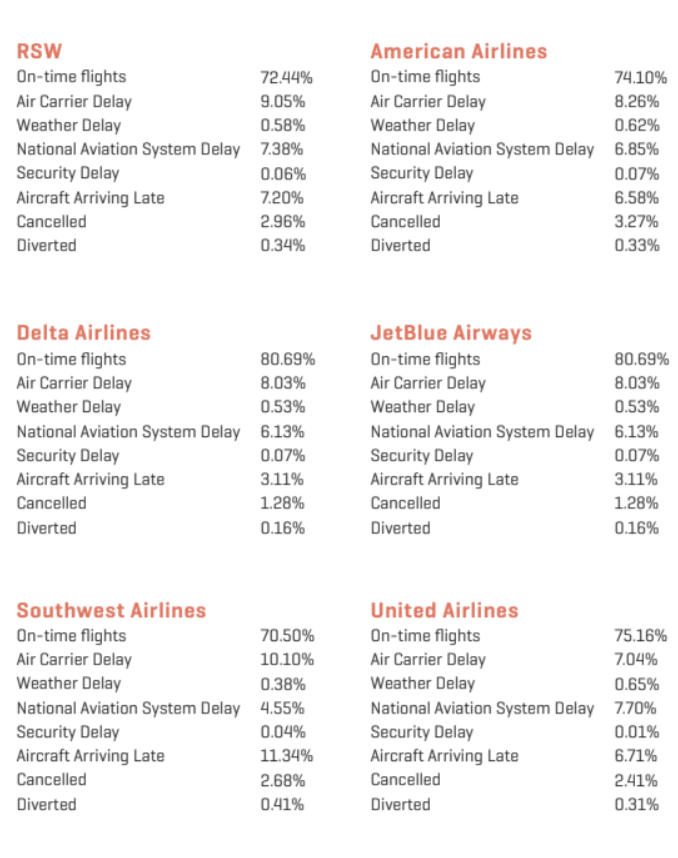

The top five airlines passengers fly at Southwest Florida International Airport are Delta, Southwest, American, JetBlue and United. Here is a look at the percentage of flights canceled or delayed at RSW from June 2021 to June 2022, according to the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics.