Editor’s Note: This story originally published in the October issue of Gulfshore Business magazine, which was printed prior to Hurricane Ian making landfall Sept. 28 in Southwest Florida.

Jamie May shows off the 80-page pamphlet from his Fifth Avenue South office in the ritziest part of downtown Naples. The pamphlet has a glossy cover showing an immaculate green lawn, a new sidewalk, a crystal-clear swimming pool and a 300-unit, Mediterranean-style apartment complex called Las Palmas in the background. There are palm trees and a blue sky mixed with peaceful clouds tinted pink from the sunrise.

“Can you find it?” May asks. Not yet.

The pamphlet’s pages are filled with facts: Las Palmas was built in 2021 on 23.84 acres. It has 12 three-story buildings, four two-story townhomes and one single-story clubhouse with a fitness center. The apartments range from 650 to 1,678 square feet, and the average rents started at just below $2,000 per month. It’s at 11900 Marquina Blvd. in central Lee County, east of Gulf Coast Town Center and Interstate 75, just south of Southwest Florida International Airport and Alico Road, the epicenter of the region’s growth.

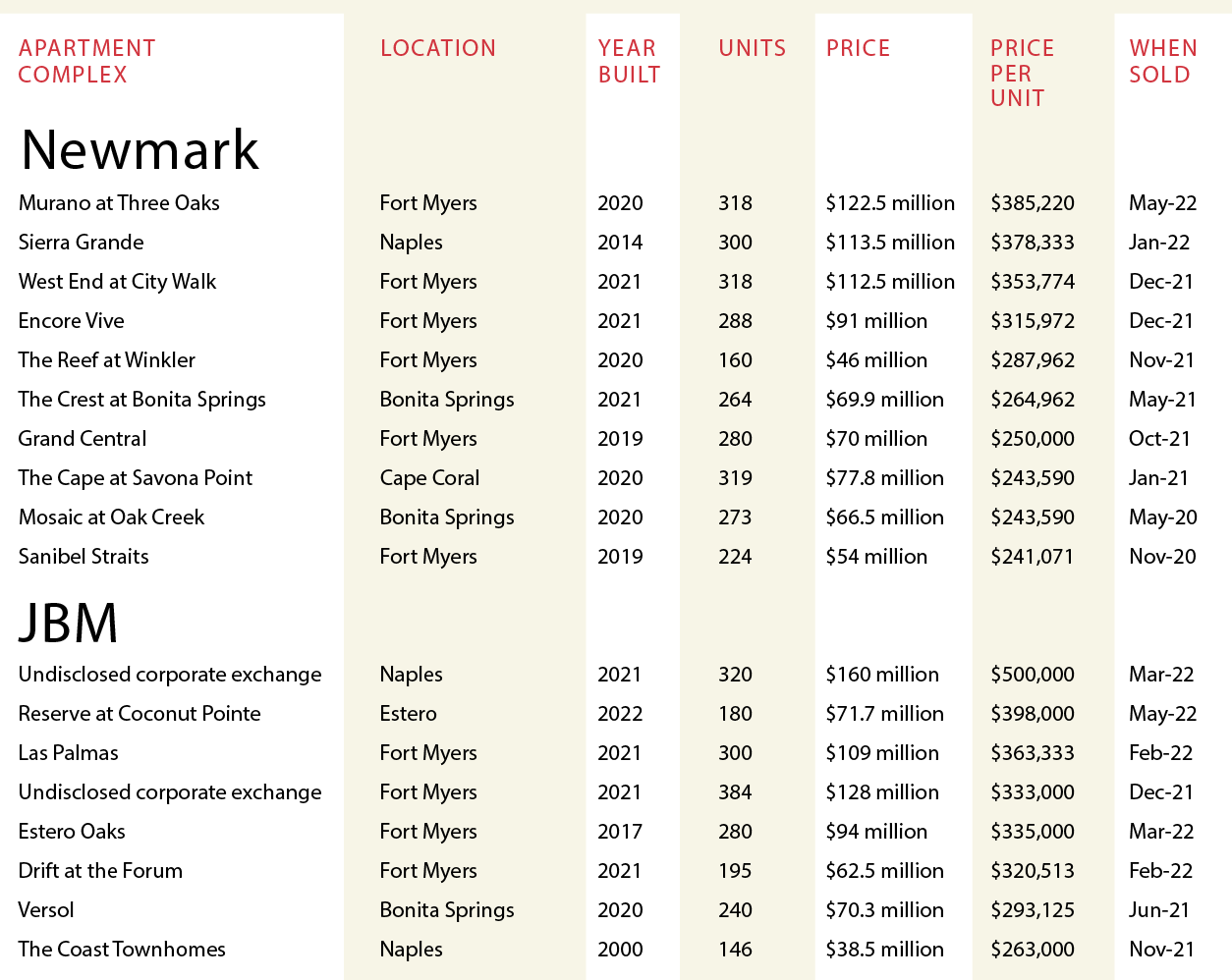

In February, May and his team of five colleagues at the JBM brokerage firm sold Las Palmas to PassiveInvesting.com for $109 million. Benefit Street Partners funded the purchase with an $82 million loan. An outfit called NRP Group sold it after developing it with a $38.5 million construction loan from Synovus Bank in 2019.

Las Palmas became another of dozens of multifamily transactions that just keep selling, one after the other. The Southwest Florida apartment-buying frenzy roughly began in November 2020, eight months after the COVID-19 pandemic began shutting down swaths of the economy in March 2020. It’s continuing.

During 32 months, May 2017 through December 2019, there were 27 Southwest Florida apartment complexes of at least 100 units that sold for a combined $1.5 billion. The 9,004 units averaged about $166,592 each in value.

During 30 months between January 2020 and June of this year—including an eight-month, early-pandemic gap with few sales—there were 33 such complexes that sold for a combined $2.6 billion. Those 9,805 apartment units averaged $265,170 in value. That data was provided by the competing brokerage firms of JBM and Newmark and matched.

This means the value of a Southwest Florida apartment unit has increased by about 60% since COVID-19 began.

Theories abound why there have been such dramatic increases in these investments, including a rush to move to the region to escape northern lockdowns and an influx of cash into the development sector from government-assisted, personal protection loans. There’s another, simpler reason: The developers are looking to recoup their investments and propel themselves with their profits to fund the next projects. To do so, they’re going to hire experienced brokers who can sell their creations for top dollar.

Achieving these multi-million-dollar deals takes time, effort and, of course, a ton of money. It also takes developers willing to endure running the gauntlet of an apartment development cycle.

THE GENESIS MOMENT

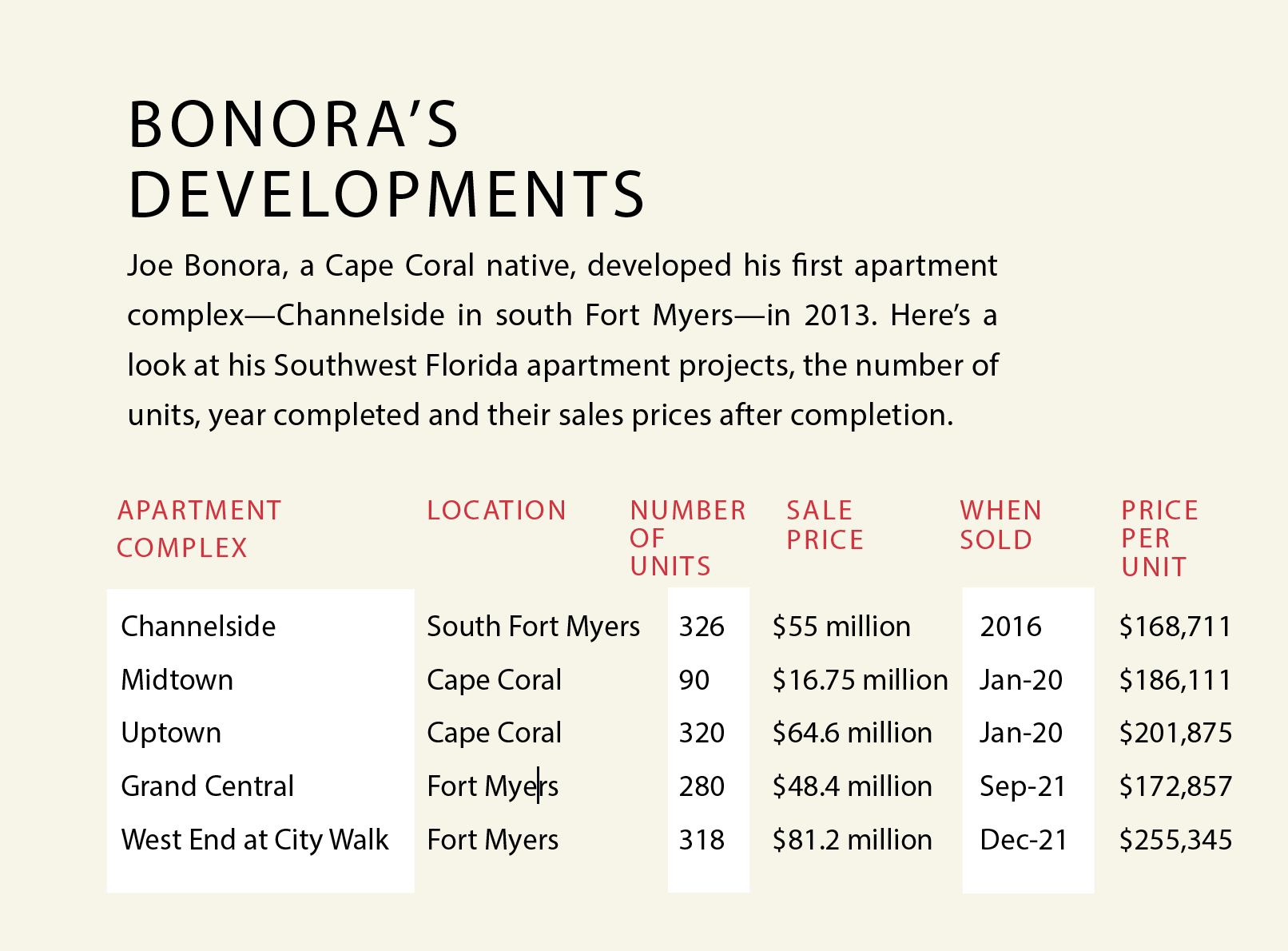

From July 2014 until December 2021, the apartment cycle took place for West End at City Walk, a 318-unit Fort Myers complex developed by Cape Coral native Joe Bonora.

In 2014, the site was 7.8 acres of raw land that once housed a decaying shopping center that had been razed, then sat dormant during the Great Recession. Bonora’s company got it under contract in December 2017 and bought it in February 2018 from Madison Avenue Investment Group for $7 million. Thereafter, construction began.

In December 2021, Tyler Minix, a broker with Newmark, sold the fully leased and completed complex for $81.2 million, a price that would have been even higher had Bonora not kept an ownership stake in it. ApexOne, a Houston-based investment company, made the bulk of the purchase.

While the closing takes seconds with the signing of the paperwork, getting brokers such as Minix and May to that moment takes years—about four years in the case of West End at City Walk.

First, land brokers including Phil Fischler and his team at Fischler Property Company of Fort Myers are often at the inception of these projects. Back when there was just dirt on the ground.

“A large majority of these apartment complexes are built by developers who are coming here from major markets,” Fischler says, “like Tampa and Dallas and throughout the Midwest. They come to companies like mine to understand the growth trends. Is the development going where you can’t see it on the ground today? They want to know where the roads are going to be widened, where the utilities are going to be extended, or maybe where a Publix has been approved, but it hasn’t been built yet.

“We help them get up to speed on the zoning and the land use. We help them get approvals. They’re dealing with environmental situations. They look to us to help them quickly get up to speed on all of those details so they can put together a game plan and start evaluating the sites. That helps them decide which sites are a go, and which are a no-go.”

While it takes Minix or May about half a year to market and sell a finished and fully leased apartment complex, it takes Fischler longer to shepherd a developer from identifying a piece of raw land to purchasing it prior to beginning construction.

“Way longer,” Fischler says.

The path to breaking ground on an apartment complex begins with four steps, Fischler explained.

1. Negotiate a purchase contract between the developer and the landowner. That usually takes three to four months.

2. Due diligence period. This entails exploring whether the site has wetlands, environmental or other issues involved, such as the presence of endangered species. This can take at least 180 days.

3. Permitting process. In Lee County, it can take eight to 16 months to apply for a building permit. “Only after that time will they close on that property,” Fischler says of the developer.

4. Construction. That can take anywhere from 12 to 24 months, depending on the size of the apartment complex.

“I’ve had some transactions that have gone five years,” Fischler says. “There’s considerable risk that these developers take on. To find the land, study it and make sure it’s suitable, build the project, then lease it up to where Jamie May or Tyler Minix can sell it.”

Fischler and his team are working with Zimmer Development out of North Carolina on two current projects. One is the 275-unit First Street Village in downtown Fort Myers. The other is the 296-unit Inspiration at South Pointe off College Parkway on what had been a goat farm. That project has cleared permitting and is on the verge of breaking ground.

Back in 2017, broker Alex Henderson, now a colleague of Fischler, began working with Zimmer on what would become three separate projects. The 432-unit Oasis at Surfside in Cape Coral was completed in 2020; the other two are under construction and took longer for various reasons. At South Pointe, the reasons included needing to rezone the site from agricultural land.

“Around the same time we had Surfside under contract, we started looking at the goat farm site,” Henderson says of the 13 acres. “We went into about an 18-month negotiation process. We got it under contract in mid-2019. Through that process, we hired Johnson Engineering to help with the civil work and land planning. We determined that it would be worth spending the extra time and money to expanding the mixed-use overlay, which is a component of the future land-use map. That was a timely process. There was an entire rezone that needed to occur.”

Zimmer had been eyeballing the land since 2017. It finally closed for $6.7 million in May 2021. Zimmer had to pay at least an extra $1.3 million to the Lee County government to receive the bonus density on the property, Henderson said. He called it a “pretty standard real estate development deal.”

Companies such as Zimmer and Bonora’s Catalyst use the revenue from preceding projects to fund the next ones.

BONORA AIMS BIG

Bonora is Southwest Florida’s rare homegrown apartment complex developer. He graduated from Cape Coral Elementary, Caloosa Middle School and then Cape Coral High School. A college dropout, he embarked on a real estate career in which he saw an opening to do something that wasn’t being done in the early 2010s because of the aftershocks of the Great Recession.

In 2013, Bonora’s company paid $4.5 million for the land that would become Channelside, a 326-unit apartment complex in south Fort Myers off McGregor Boulevard and Pine Ridge Road. His company sold it in 2016 for $55 million, and the property changed hands again, for $65.2 million, in August 2019.

“My first project, Channelside, that’s when I got the bug,” Bonora says. “I knew then that multifamily was going to be my thing.”

After Channelside, Bonora developed Midtown in Cape Coral (90 units), Uptown in Cape Coral (320 units), Grand Central in Fort Myers (280 units) and then West End at City Walk (318 units).

That’s 1,434 apartment units built during the last decade that since have sold for a combined $265.95 million.

“Channelside is really what kicked off, locally, a lot of the multifamily projects,” says Matt Simmons, a property appraiser with Maxwell, Hendry & Simmons in Fort Myers. “It was really the first new apartment complex of any size or scale to be built after the destruction of 2006, ’07, all the way up through 2010. It took a long time to flesh out the asset classes, where the bottom was. There was this understandable hesitance to bringing a new product to the market. Joe Bonora delivered that project. It was so well received; it really set off the signal to other developers that it was time to do these again. It paved the way for others to realize there’s demand for new multifamily.”

Bonora’s status as a homegrown developer is rare because most local development companies just don’t have the financing to back these big projects.

“The way development works now, these things are incredibly cash-intensive,” Simmons says. “It’s not as if somebody can just run down to the bank and get a loan and just build a bunch of apartments. It’s really competitive. It’s really professionalized. A lot of these are built on Excel spreadsheets.

“It’s all being driven—hard—on the financials. On what will maximize the returns. It’s private equity, it’s syndicated investment deals, it’s people who do this kind of thing over and over again. This is not mom-and-pop development. There’s nothing that prevents local people from doing these things, it’s just there’s a lot of horsepower required to build 100 or more units. You’re talking about a lot of money and a lot of expertise.”

Up next for Bonora: Montage at Midtown near downtown Fort Myers. That’s a 321-unit complex that is nearing the end of the permitting phase and should break ground by early 2023.

Bonora isn’t just developing in his hometown, either. He’s also working on a 287-unit apartment complex in Bradenton, a $90 million riverfront construction project that will have synergy with an adjacent $50 million arts center.

“I had a basic understanding of construction and development,” Bonora says of the beginning of his career. “But what I’ve figured out is a lot of what we do is coming up with a theme and then managing that theme. Contractors, designers, planners, all of the people that you need on board for a project, need to be on board with that theme.

“A big component of development is understanding the capital. How to make the numbers work is a big part of it. Quite honestly, I spent as much time as I could learning how to do business on my first project. That helped me more than anything. I learned every part of that process.”

Now that Bonora has been able to get into the rhythm of developing, fully leasing and selling these apartment complexes, he’s looking to stay invested in some of them for the long term. He’s evolving.

“Most developers, you’ll develop it,” he says. “You’ll invest in it, and you’ll have investors who will have ownership in it. You put the bids together. You make sure you can get it leased up. Then you sell it. I’m going to try to hold onto them for the longer term. I just feel the growth of the market.”

MINIX HITS THE MARK WITH NEWMARK

Minix, one of the region’s top brokers with Newmark, graduated with a finance degree from FGCU and later received a master’s in real estate from the University of Florida.

Six years ago, he evolved into brokerage and began specializing in multifamily investment sales in Southwest Florida. He said it took him about three to four years to get a good feel for the business—and he came into his own just in time for the most lucrative real estate market the region had ever seen. “I love my job,” Minix says. “I am fortunate to work with the best team in the industry and get to work with our amazing clients.”

Minix needs about six months from the initial marketing of a property to closing a deal. There are usually 15 to 25 bidders on various apartment complexes; the number of suitors depends on the location, the size, the age and other factors.

“We market the asset for four to five weeks, conducting property tours and presenting the asset to potential buyers,” he says. “The initial round of offers are due at the end of the marketing period. The best and final offers are due a week later. We interview the best and the finalists. We analyze and verify the underwriting, financial assumptions and source of equity. We perform due diligence on each investor’s transaction history, historical performance and ability to close.”

These are extensive background checks. JBM does them, too.

MAY CLOSES THE DEAL

For May and his team, the methodology is similar. But instead of working for a Park Avenue, New York-based company with about 170 offices and 6,500 employees, he presides over a nimble team of just six.

“Wealthy people are migrating to the west coast of Florida,” May says. “It’s like the new frontier. The cost of housing is far more affordable compared to the east coast. Southwest Florida was sleepy until about 10 years ago. Developers can’t move fast enough to satisfy the need.”

Apartment complexes have been leasing to 75% capacity before they’re even finished with construction, May said.

“We typically list them at 25-to-50% leased,” he says. “It’s a value-add strategy for the buyer. We’ll get 30 to 50 offers on an asset. We’ll give people a ‘whisper price.’”

As the interest from potential buyers intensifies, that whisper price escalates. That’s when May and his team narrow down the candidates to buy the apartment complex. The original suitors usually get cut to three finalists, resulting in another price escalation for the apartment complex.

As this year began, the per-unit price—the preferred method of discussing these sales by the brokers—kept rising, especially in Lee County.

Just a few weeks after the 288-unit Encore Vive at the Forum in Fort Myers sold for $91 million at a Lee County record $315,000 per unit in December 2021, the record fell again. The 194-unit Drift at the Forum sold for $62.5 million in February. At $320,512 per unit, that made it one of the biggest sales of early 2022. A Miami-based investment company bought that one. Since, that per-unit benchmark has been eclipsed again—and again.

Back in May’s office, he’s still wondering if a visitor has found one of his marketing ploys.

“You find it yet?” May asks again. Still not yet.

Turning more pages of that Las Palmas pamphlet, the JBM logo appears, Photoshopped onto paintings, big-screen TVs and even the display screens of the four treadmills on page 13, showing off the “24-hour, state-of-the-art fitness center.”

“I started the business out of a bedroom,” says May, a Boston University graduate with degrees in finance and real estate. He now owns a home in Port Royal, the most affluent neighborhood in Naples. “I was riding a bike to do all of these deals.” Not anymore. Nowadays, he’s driving his 14th Ferrari.

“All we do is multifamily,” he says. “Generally speaking, I try to sell 200 units or more. Our niche is new market development. Once it leases up, we come in and sell it for a profit.”

On pages 22-23 of that pamphlet are the “notable one-mile demographics” for Las Palmas. The average, one-mile household income for central Lee County checks in at just under $200,000. The average, one-mile net worth is $2.54 million. These aren’t just random facts; they’re demographics that inspire investors to take considerable risks when deciding to purchase properties; because after they buy the apartment complexes, they need to keep them full of tenants to continue to profit from their investments.

FINDING THE FERRARI

But back up. There it is, on page 21, near the lower left corner. May’s bright red Ferrari is driving through the Las Palmas parking lot.

JBM includes the Ferrari in each of the apartment complex promotional pamphlets it produces. It’s kind of like the “Where’s Waldo” cartoon, trying to find the Ferrari. It’s an in-house touch, May said, one he hopes differentiates his brokerage company from others. In the competitive arena of apartment complex developments, standing out helps.

Rising interest rates, inflation, supply-chain issues with construction, permitting backlogs, cash shortages—they’re all putting a dent into developing. But land brokers such as Fischler, developers such as Bonora and brokers such as May and Minix remain undaunted—because shelter remains a primary need.

“Sales volume has slowed,” Minix says. “However, the long-term outlook for Southwest Florida multifamily remains strong. Investors continue to seek high-quality properties throughout Southwest Florida.”